Conflict is part of every workplace. If done right, conflict can be productive, improving your workplace results and relationships. But conflict can also be toxic, and the way our brains are wired means unhealthy conflict behaviors are often our default.

The Wiley ebook Under the Hood: The Secret Engine That Drives Destructive Conflict (PDF) examines toxic conflict responses, why they arise, and why so many workplaces fail to deter them. It then presents a science-based, scalable solution.

First, let’s take a look at how our brains can stand in the way of productive workplace conflict.

Problem #1: We do things we know aren’t helpful.

Why do we gossip? Why get sarcastic or petty? Why give a coworker the silent treatment? We know these behaviors are never productive, yet—especially in conflict situations—we find ourselves acting in these and other destructive ways. Under the Hood puts it this way:

“Conflict brings out some pretty erratic, counter-productive, and often downright uncharacteristic behavior in us. It taps into our primal impulses in a way that few other situations can. Because our real driving motives are inaccessible in the heat of the moment, we’re almost powerless to get them under control, resulting in toxic or damaging knee-jerk responses. We exaggerate or stonewall or exclude others when this is almost certainly not the type of person we consider ourselves to be—definitely not the image we want our parents, children, or mentors to have of us.”

The fact that we can’t explain why we are doing it is the root of the problem. It’s coming from a subconscious place, and as such, can feel impossible to change. How do you fix what you can’t even see?

Under the Hood examines some “hidden but undeniable benefits” these behaviors provide. They feed us in ways that keep us coming back to them, especially when emotions are running high:

- Gossip gives you validation and the power of being the one with insider knowledge.

- Sarcasm allows you to attack someone, then activate the “just kidding” excuse.

- Stonewalling makes you feel righteous and lets you avoid conflict.

- Exaggerating lets you make a minor situation sound as bad as it feels to you.

When we think of it rationally, we know these behaviors are unproductive. But in the moment, they just feel good. That feeling of reward, though, is short-lived, so we must reach for it again and again.

Problem #2: Unproductive conflict drags down the workplace.

Conflict can have a staggering impact on efficiency and engagement. Wiley surveyed over 12,000 employees about their experience with workplace conflict and found that:

- Seventy percent of managers said interpersonal conflict negatively impacts efficiency.

- The average manager spends 13 hours per month dealing with conflict.

- Forty percent of workers have left a job as a direct result of unhealthy interpersonal conflict.

Forty percent! Two out of every five employees have actually left jobs because of this. Must we accept a number so high as the price of doing business? Many organizations are hesitant to get into the murk of helping people with their internal lives. We’re not therapists, they think, and then deal with toxic conflict by telling employees, “Be more professional.” OK, but how?

It’s rare for people to learn actionable methods for conflict management at any point in their lives. And we can’t rely on people’s good instincts, because there’s so much going on “under the hood” during conflict situations. These are the times our instincts serve us least well.

Problem #3: Our real motivations are hidden.

Under the Hood gives two examples (there are dozens more) of how hidden and counterintuitive our conflict responses can be.

Emotional indulgence

Emotions can have addictive qualities. That’s why wallowing in self-pity or stewing in anger gives us a temporary feeling of satisfaction, but then leaves us feeling worse than before.

Emotions can have addictive qualities. That’s why wallowing in self-pity or stewing in anger gives us a temporary feeling of satisfaction, but then leaves us feeling worse than before.

Under the Hood summarizes a fascinating study (Westen et al., 2006) utilizing fMRI scans of people who were strong conservatives or strong liberals. When asked to generate arguments against their own political views, the parts of the brain that were activated involved higher-order and executive reasoning: the prefrontal cortex. When asked to come up with arguments against the other political party, there was much less prefrontal cortex activity. Instead, the parts of the brain that lit up were those that process disgust—and, more surprisingly, pleasure. Disgust and pleasure may seem at odds, but they combine into something very familiar to most of us: self-righteousness.

If you’ve witnessed or participated in political arguments on social media, you’ve likely seen some great examples of emotional indulgence and the chasing of negative emotions. And the workplace is not immune to this emotional addiction. The stonewalling, the gossip—on some level, it feels good. We tell ourselves we have to do these things, perhaps in the name of some vague justice, without acknowledging our satisfaction in them.

Emotional avoidance

Sometimes we indulge in emotions; sometimes we avoid them. A common example of this is choosing to get angry when what you’re actually feeling is hurt. Say someone gives you critical feedback when you know you haven’t done your best on a project. Rationally, the feedback is probably fair, but anger may be the first and easiest instinct for your brain. Then you don’t have to think about your sense of worth or any personal goals you’ve failed to meet. This is all tied up with insecurity (see The invisible root of workplace dysfunction). Anger externalizes the problem, so the fault no longer lies within us.

Maybe anger isn’t your default avoidance technique, but instead, despair, indifference, or anxiety is. Once again, the biggest issue is that we don’t even recognize we’re practicing emotional avoidance. What emotional indulgence, emotional avoidance, and other counterintuitive conflict responses have in common is that “the real motivation for our conflict response is far from the rationale we recite to ourselves.”

Problem #4: There are so many types of unhealthy conflict responses.

Every brain has its own emotional addictions. If it’s not gossiping or stonewalling, it could be withdrawing, passive aggression, belittling, overpowering, drama, hypercriticism, caving in, dismissing opinions, finger-pointing, and on and on. You almost certainly have a go-to conflict strategy that doesn’t make you proud.

Every brain has its own emotional addictions. If it’s not gossiping or stonewalling, it could be withdrawing, passive aggression, belittling, overpowering, drama, hypercriticism, caving in, dismissing opinions, finger-pointing, and on and on. You almost certainly have a go-to conflict strategy that doesn’t make you proud.

If all toxic conflict looked the same—if we all defaulted to the same bad habits—it would be so much easier to address within an organization. Since that is not the case, any solution needs to account for the myriad and very personal ways people react poorly to conflict.

CBT: A solution within reach

That was a lot of bad news about how our brains process conflict. But there is also some incredible news! Our brains can be wonderfully trainable things when we speak to them in their own language.

In all the situations discussed above, what we do have access to is our thoughts. Thoughts trigger emotions, which trigger behaviors. So we must recognize and manage thoughts before they lead us astray. In the therapeutic field, this is called Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), and there is a ton of research proving its effectiveness.

How Cognitive Behavioral Therapy works

According to Under the Hood, “CBT works because the same brain mechanism that leads to emotions coming out sideways also works in reverse. Unhealthy automatic thoughts can lead to unproductive emotions. But conscious, positive, or neutral thoughts can also help us regulate our emotions.”

Step 1: Recognize unhealthy thoughts. This is hard, because they tend to be unconscious, at least at first. To practice this skill, when you feel a strong emotion, try to find the thought driving that reaction. Once you locate the thought, you can examine it:

- Is this thought actually true?

- Is there another way I could look at the situation?

Step 2: Reframe the thought. Reframing replaces the initial thought with one that’s more realistic and productive. For example:

- Automatic thought: “They have no idea what they’re talking about.”

- Reframed thought: “They’re coming at this from a different angle than I am.”

Step 3: Choose a more productive response. “Once the thought has been reframed, our emotional reaction tends to realign itself with reality; to be proportional to the actual threat in the situation. We can go from lashing out to assertively stating our needs. We can go from retreating back to our desk to making sure the other person knows we’re offended.”

CBT + DiSC = Everything DiSC® Productive Conflict

Wiley took the elements that make CBT so effective and created a personalized, scalable, empirically validated training program. They spent two years developing and testing a course that takes the learner’s personality into account and helps them understand the type of thoughts that may be particularly tempting.

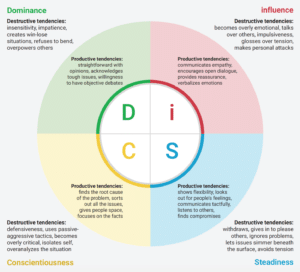

The engine behind this personalization is the Everything DiSC® model, which helps participants quickly understand their own destructive and productive tendencies during conflict. For example:

- D styles tend toward impatience, but are also willing to acknowledge tough issues.

- i styles may become overly emotional, but also communicate with empathy.

- S styles tend to let issues simmer, but are also good at finding compromises.

- C styles can be defensive, but can also help by focusing on the facts of a situation.

Everything DiSC Productive Conflict is not about a step-by-step conflict resolution process. Instead, it provides personalized techniques for ongoing mental practice. The more you and your team members practice, the better you will be able to recognize toxic thoughts in the midst of conflict and redirect them into more productive behaviors.